DISCOVERY

In March of 2017 I was out scouting for meteorites in Southern Utah near my home town of Big Water. As usual, I was having very little luck with my metal detector. While out looking, I worked my way into a wash and spotted some mud layers that didn't belong within my understanding of the geologic sequence of the area so I decided to investigate.

After moving down the wash a ways it became clear to me that I wasn't seeing the Jurassic or Cretaceous formations I was familiar with, but much more recent layers of mud and gravels that could be Pleistocene in age. These suspicions were confirmed when I walked along a bench and found a partial equine (horse) tooth. I knew the gravels were hundreds of feet above the current river level, and the tooth had been impacted with gravel, so it had to have come out of the gravels. I made the safe assumption that the gravels this far above the current river were at least thousands of years old and possibly tens of thousands of years old.

I walked along the bench some more and found other strange flat pieces of rock that looked like enamel but I couldn't make sense of. Figuring I had seen the best this place had to offer with a few broken tooth fragments, I decided to head back up the wash towards my truck and check out one more exposure on the way. As I rounded a corner into this last mud layer exposure, I spotted a bunch of these strange flat enamel-like rocks still arranged into a pattern:

I stared at these flat sheets sticking up in an oval formation for a few seconds then something clicked in my head. This was a highly eroded mammoth tooth! I couldn't believe what I was seeing, but was absolutely confident in my identification. I had seen enough of these teeth to know that they were arranged in folded sheets of enamel with dentin between them. The eroded tooth has lost most of the softer dentin (white particles on ground) and the enamel sheets were mostly still intact and still in the oval shape of a mammoth tooth.

I poked around the exposure some more and spotted a few larger bones scattered around with some clearly still buried in situ. At this point I knew I had an important Pleistocene site and decided to take images, GPS coordinates, and report it to a paleontologist I know in the area - Dr. Alan Titus.

Dr. Titus and I visited the site with a another specialist in Pleistocene fauna, Dr. Greg McDonald, who confirmed that I had found a location with at least a few different species of animals including mammoths, canid, and bovid remains preserved. He also noted that one area of the hill had a large amount of ivory eroding out which was breaking up into small pieces at the surface. We had no idea of what age these sediments were but knew they were at least 12,000 years old, which is around the time the last species of savannah mammoth occupied this area. In this case Dr. McDonald determined we were looking at remains of Columbian Mammoths.

DATING

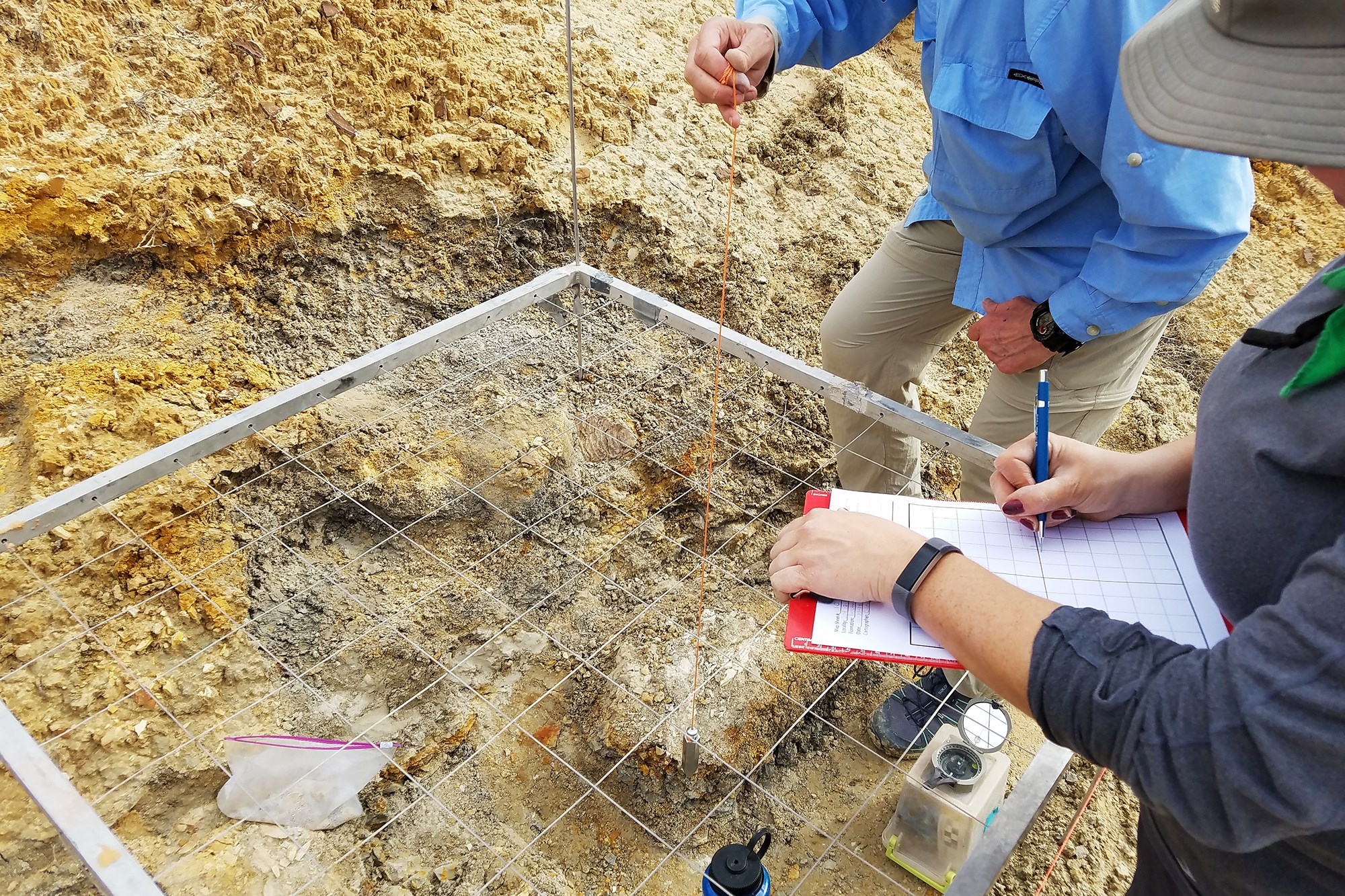

We were able to start dating work with a partnership between Utah State University and Dr. Jim Mead at The Mammoth Site. He provided a donation which enabled Dr. Tammy Rittenour (USU) to bring a student down (Evan Millsap) for some Optically Stimulated Luminescence dating samples. This form of dating was completely new to me and was neat to learn about. I encourage you to read up on it.

The dating process was a lot of fun and I got to help out on it. Unfortunately not long after graduating and moving to Alaska to work towards his Ph.D, Evan lost his life in climbing accident. He was a great guy and is missed by a lot of people.

The initial dating work by Evan put the mammoth remains around 200,000 years old which was a shock to all of us. This made these mammoth remains the oldest recovered from the Colorado Plateau. This was later refined to ~220,000 years old with more samples and further analysis.

EXCAVATION

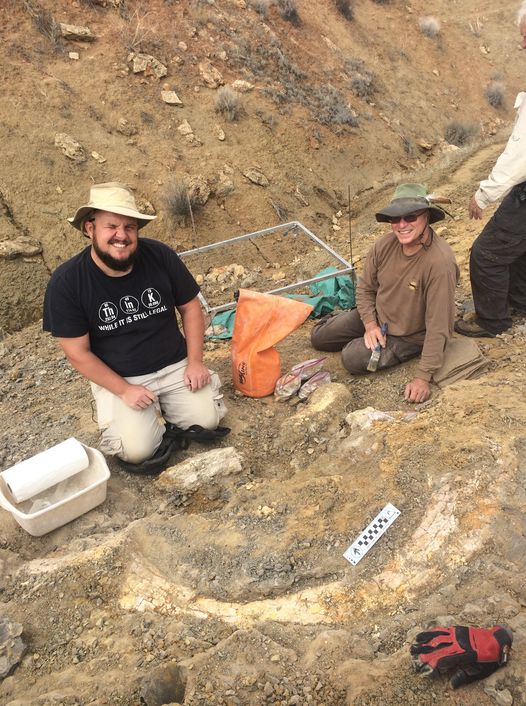

Early on, the Natural History Museum of Utah at the University of Utah agreed to procure permits to dig the site and do further research on it. We ended up cracking the site open in October of 2018. This excavation revealed a lot of new material including a very large section of tusk, a well preserved tooth, and some other bone fragments. Unfortunately a lot of the bone material had been exposed to weathering before it was buried so it wasn't in great condition. You can view a 3D interactive map of the quarry on my SketchFab page.

RESEARCH

The remains are still housed at the University of Utah. I'm not sure if any work has been done on the large jacket to remove and stabilize the contents. At Utah State University, another student of Dr. Rittenour, Noah Slade, completed his Master's Thesis on this site and the surrounding sedimentology that led to the preservation of these critters. There were many interesting revelations that came from this research.

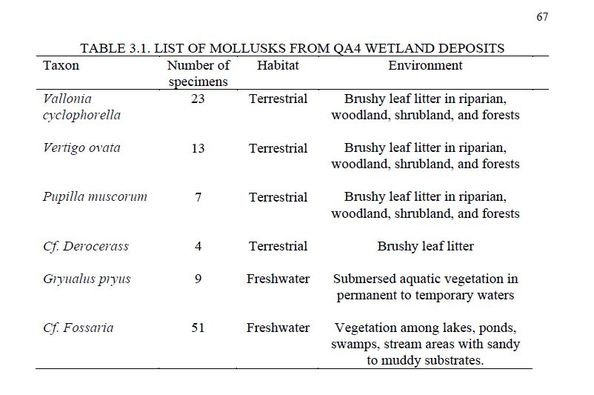

The climate at the time mammoths were living in Southern Utah was radically different than it is today. Many of the creeks ran year round and there was a lot more rainfall. Seeds to species of sedge (carex) grass were found associated with the bones which do not occupy the area today. In addition to the bones and seeds, there were 6 species of extinct terrestrial and fresh water mollusks that were recovered from the site and identified. This all helps paint the picture of a very different place 220,000 years ago. The area would have been covered in trees and tall grasslands with local creeks running year round and flooding the landscape on a regular basis providing marshy wetlands for many creatures including canids, bovids, and mammoths, to come drink and look for food. Quite a different scene than the arid landscape of today that rarely floods usually during the monsoon season.

Noah's Master's Thesis can be found here: Pleistocene Deposits of Lower Wahweap Creek and Its Tributaries, Southern Utah.